By Armine Kardashyan

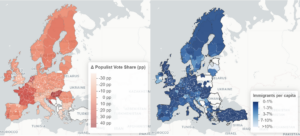

Over the past decade, populist parties have been gaining ground across Europe; as a result, they are reshaping national politics, influencing EU decision-making, and challenging liberal democratic norms. Most of the public debate frames this rise as a reaction to immigration which poses a cultural threat and erodes a perceived white, Christian European identity. Yet while populists have made immigration a salient issue in EU politics, some of the strongest surges in populism are happening in places least affected by immigration. In Portugal’s Alentejo region, for example, migrant inflows remain close to zero, however support for populist parties has grown substantially over the past decade – rising nearly ten-fold between 2019 and 2022. By contrast, regions like Vienna, which receive some of the highest migrant inflows in Europe, show far weaker populist reactions.

This disconnect challenges the assumption that migration alone fuels populism. If support for populist parties rises even where immigration is negligible, then there must be another underlying driver. One explanation is that Europe is facing a severe demographic crisis. Fertility rates across the continent are far below replacement levels, workforces are shrinking, and age-dependency ratios are rising sharply, placing increasing fiscal pressure on pension and welfare systems. Governments are already being forced to make difficult structural adjustments, such as France’s attempts to raise the retirement age, in order to stabilize pension and labor-market systems. These pressures heighten social and economic insecurity, creating fertile ground for political narratives centered on threat, protection, and decline. This context gives rise to an important question: to what degree do migration and demographic pressures contribute to rising populist support across European regions?

To answer this question, I use panel data from 2015-2023 and apply a high-dimensional fixed-effects model to isolate the joint effects of demographic pressures and migrant inflows on electoral outcomes. My unit of analysis is European Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS-2) which are statistical subregions with between 800,000 and 3 million inhabitants. Using these subregions allows me to capture within-country variation and heterogeneity that would be obscured by national data.

I find that immigration and demographic stressors each contribute to increases in populist vote share, but they do so through separate channels. Holding other variables constant, a one-percentage-point increase in the migrant share of the population predicts a 0.13-point rise in populist vote share, indicating that even modest inflows are associated with measurable electoral gains for populist parties. Demographic pressures independently shape the same outcome. Regions with lower fertility rates or higher old-age dependency ratios have also experienced larger increases in populist vote share over the same period, suggesting that aging and population decline generate political discontent even in the absence of migration. Importantly, however, these two trends do not reinforce one another. Rather than amplifying migration’s effect, aging and fertility decline appear to operate as separate structural sources of populist support, each contributing to the broader rise in populist voting through its own mechanism.

Figure 1. Change in populist vote share in 2015-2023 by NUTS-2 region vs Immigrant share in 2015

This challenges a common assumption in liberal policy circles – that low-fertility societies must eventually embrace immigration out of necessity. In policy debates, this argument is often reframed in economic terms where declining fertility is presented as making immigration fiscally necessary for the sustainability of welfare states. Yet necessity does not guarantee political acceptance. Regions experiencing demographic contraction are not uniformly welcoming migration as a demographic fix. Instead, many turn toward parties promising protection, restoration, or reversal. The two pressures of aging without migrants and migrants without aging generate distinct grievances that converge politically in support for populism, but neither intensify nor mollify one another. Immigration does not inherently exacerbate the pains of demographic decline, nor does demographic decline eliminate nativist backlash. Immigration may help fill labor gaps, but it does not automatically relieve demographic stress. If anything, it fuels a search for alternatives that bypass immigration entirely.

Historical cases make this pattern tangible. Since the Syrian refugee crisis in 2015, populist parties have experienced rapid vote share increases in several European countries. Marine Le Pen’s National Rally has expanded in French regions marked by economic stagnation and aging electorates. Geert Wilders secured historic victory in the Netherlands despite relatively moderate migration levels, reflecting the salience of demographic and cultural insecurity rather than direct exposure to migration. Viktor Orbán consolidated power with his party Fidesz in Hungary after years of demographic decline rather than inflow pressure1. These national cases suggest that the regions most politically reactive are often those least demographically equipped to withstand further population loss.

This creates a two-sided vulnerability. Economically, Europe will require migrant labor to sustain pensions, healthcare systems, and manufacturing sectors as native cohorts retire. Politically, however, as aging demography led to support for populist parties, anti-immigration sentiment intensifies precisely at the moment when migration becomes most necessary. This is Europe’s defining paradox: the continent will need more migration to weather aging, yet voters in aging places grow less willing to accept it.

Such conditions demand policy response beyond the migration frame alone. Fertility decline and labor shortage must be treated not only as demographic events, but as democratic-stability variables. Family support policies, childcare investment, and housing affordability play as direct a role in political resilience as asylum quotas or integration programs. Equally important is geographic targeting. If populism rises in regions defined by demographic decline even when migration is low, then EU cohesion interventions must not rely solely on economic indicators, but incorporate measures of demographic vulnerability itself.

The stakes are not merely electoral. An aging continent has implications for productivity, strategic autonomy, and defense capability; the composition of the European labor base affects everything from industrial renewal to green transition planning. If the working-age population continues to contract while political resistance to pro-migration policy expands, the EU may face its most significant structural challenge since enlargement. How Europe responds to demographic decline will shape not only economic growth, but democratic legitimacy and geopolitical stability.

1Eurostat (2023), Demography of Europe – 2023 edition

|

Article by Armine Kardashyan ’26 |

|