By David Lyu

In fiscal year 2025, U.S. Customs and Border Protection seized more than 12,000 pounds of fentanyl – enough, at the DEA’s estimated lethal dosage of 2 milligrams, to kill the entire U.S. population eight times over. This number raises a critical question: are synthetic opioids like fentanyl adding to the death toll, or are they displacing traditional opioids like heroin and morphine due to their cheaper cost and higher potency? The answer has profound implications for policy making.

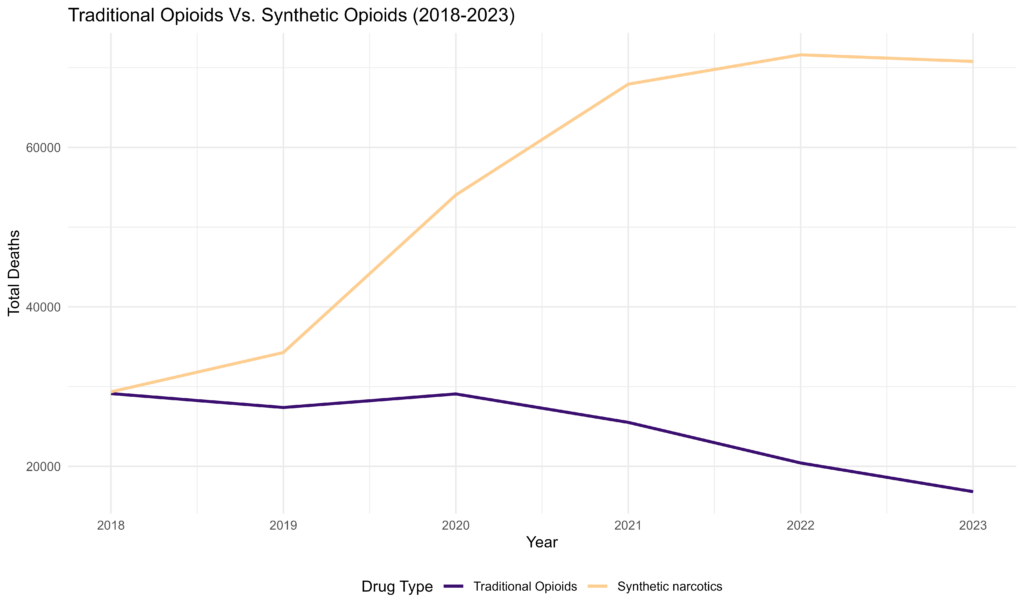

Using CDC mortality data from 2018 to 2023, I tracked overdose deaths across all 50 states, separating out death from traditional opioids (opium, heroin, morphine and methadone) and synthetic opioids like fentanyl. From these two categories, I was able to visualize the national trend in overdose mortality.

Figure 1: Total number of deaths in the United States caused by either traditional or synthetic opioids.

The data reveals a sharp divergence: traditional opioid deaths declined from 28,000 to 18,000, while synthetic deaths rose from 32,000 to over 70,000, more than doubling over five years. But diverging trends alone don’t prove one form of overdose is substituting for the other. To provide more granular evidence, I examined state-level variation in where synthetic opioids deaths were rising. Specifically, when a state has a higher than baseline traditional opioid death rate, does it subsequently see more synthetic opioids death?

The answer is yes. States experiencing higher traditional opioid deaths in a given year see a substantial increase in synthetic deaths one and two years later. Using numbers to showcase the scale: for every 10 additional traditional opioid deaths per 100,000 population in a state, synthetic opioid deaths increase by roughly 3.4 per 100,000 population the following year, and by 8.2 two years later.

This result doesn’t give us a definitive answer that individual users are switching from heroin to fentanyl. Aggregate data can’t tell us that. What’s happening could be more subtle. Perhaps both trends respond to the same underlying factors – worsening economic conditions and limited healthcare access, or deepening addiction that makes users more willing to try stronger and cheaper alternatives.

What the evidence does reveal is that factors making a community vulnerable to traditional opioids predict vulnerability to synthetic opioids within a two-year window. The following interactive maps visualize this effect.

Figure 2: State level opioid overdose death per 100,000 population, year 2018-2023. Top: traditional opioids, bottom: synthetic opioids. (The 2018 synthetic death data in ND and MT is NA due to CDC data collection)

As we observe in the top map (traditional opioids), the top states with high death rates (dark red) are in the Appalachia region centered around West Virginia – what distinguishes the Appalachia is its large coal mining industry which was heavily impacted by China’s entrance into the WTO. Research from the National Bureau of Economic Research has positively linked the region’s high opioid mortality rates with coal mining due to the high workplace injury rates and subsequent prescription of highly addictive opioid painkillers.

The bottom map reveals a similar pattern where states with elevated traditional opioid mortality in earlier years have high synthetic opioid deaths in later years. The regression analysis confirms this relationship, with Appalachia experiencing elevated synthetic opioid mortality alongside its traditional opioid crisis.

This dynamic suggests a fundamental challenge with supply-side drug policy. It implies that reducing one substance’s availability may not address the underlying demand, which can switch to alternatives. Meaningful progress in substance abuse mitigation requires addressing the root causes of such dependency – pain management alternatives, economic opportunity, and the access to addiction treatment.

Fifty years into the War on Drugs, the fundamental drivers of addiction and overdose haven’t changed. Breaking this cycle requires moving beyond supply-side solutions to address why communities remain vulnerable in the first place.

|

Article by David Lyu ’27 |

|