By Caleb Rasor

Firearms are a divisive topic in American political discourse, and opinions vary widely on the extent to which they should be regulated. Despite the highly polarized nature of gun legislation, policymakers can make more informed decisions by understanding which regulations are empirically proven to save lives and which are not.

In service of this goal, I evaluated the efficacy of one particular firearm regulation: mandatory waiting periods between the purchase and receipt of a gun. I compare the effects of this legislation in urban versus rural counties, finding that the 2007 repeal of a waiting period law in Missouri resulted in a rise in suicides only in rural counties and not urban ones. Here, I discuss the reasoning and methodologies behind my analysis, potential explanations for this phenomenon, and takeaways for policymakers who are interested in re-evaluating waiting period legislation.

Methodology and Data

There are two reasons that I focused specifically on waiting periods. First, waiting periods for purchase of a firearm are relatively well-supported across the country, with one representative poll of American adults finding that 77% endorse such legislation. But more importantly, waiting periods represent a potential method of reducing gun suicides, which take the lives of 27,000 Americans annually.

Most suicide attempts are the result of fleeting moments of ideation rather than long deliberation. A study involving 153 survivors of suicide attempt found that 71% deliberated for less than one hour before attempt, and virtually all deliberated for less than a week. For individuals in such moments of temporary mental distress, a multi-day waiting period to acquire a firearm potentially allows them to seek help from family, friends, or mental health professionals before taking their own life. The repeal of such a law could result in a rise in firearm suicides by allowing people in distress who don’t already own a gun to access one within minutes, no questions asked.

In order to determine the effect of a waiting period law on gun suicides, we can’t simply compare states with that law to those without – after all, the states that implement gun regulations often differ in many ways from those that do not (for example, they are more likely to be highly urban and politically liberal). For that reason, the best way to assess the efficacy of a gun law is by comparing the relative change in the difference between death rates of a state that changes its law and other states that do not. This is known formally as a difference-in-differences analysis, and it statistically adjusts for state-level “base rates” of firearm suicides as well as regional or national fluctuations in firearm suicide. For the purpose of this research, the difference-in-differences regression relies on the states of interest keeping gun laws unchanged, with the exception of a single law change under examination.

A match for these ideal conditions for analysis can be found with Missouri, which repealed a permit-to-purchase law for handguns in 2007 that had been in place for 80 years. While it existed, the permit process required both a background check and, critically, a de facto waiting period of up to seven days between purchase and receipt of the firearm. In the years leading up to and following this shift in Missouri gun laws, states bordering Missouri kept their gun laws virtually unchanged, providing stable points of comparison.

To conduct this analysis, I drew firearm suicide data from the CDC WONDER portal for the period 1999-2016 for Missouri and all of its eight bordering states. While I could not separate the data by county due to CDC suppression of small values for privacy concerns, I instead grouped within each state by NCHS urban-rural classification code (a 1-6 scale where levels 5 and 6 are considered rural counties). This allows me to overcome data suppression and determine the effects of dropping the waiting period law on urban versus rural counties. Data on state-by-year firearm laws come from the RAND State Firearm Law Navigator.

I performed a three-way difference-in-differences analysis between Missouri/non-Missouri, pre/post 2007 law change, and rural/non-rural counties. I further controlled for state and year fixed effects (essentially, adjusting for the fact that a particular state or year may be associated with higher/lower gun suicides across all counties). Standard errors were clustered by state.

Results

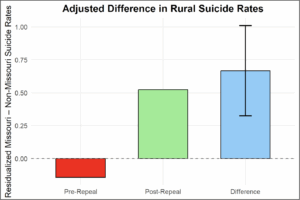

My difference-in-differences analysis reveals that rural counties in Missouri experienced an additional 0.67 gun suicides per 100,000 residents after the repeal of the de facto waiting period law relative to rural counties in bordering states. This result is highly statistically significant, with a p-value of 0.002 (meaning there is a 99.98% chance that the law change resulted in additional gun suicides compared with rural counties in other states). By contrast, the repeal had no statistically significant impact on the gun suicide rate in urban and suburban Missouri counties compared with urban and suburban counties in neighboring states. To my knowledge, this result has never before been published (although past research has found a statewide association between waiting period repeal and elevated firearm suicides).

Figure 1: Residual difference in rural suicide rates between Missouri rural counties and non-Missouri rural counties, after adjusting for year and state fixed effects. The right-most bar represents “difference-in-differences;” 95% confidence interval shows that the difference between post- and pre- repeal is significantly different from zero.

Explanation of Results

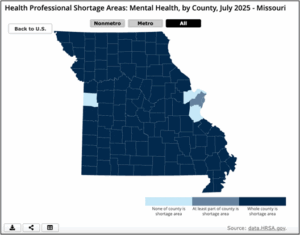

There are two main ways in which we can explain the gap in waiting period impacts between urban and rural counties, each of which are well articulated in a recent piece published in the Southeast Missourian. The first is a severe lack of mental health resources and insurance coverage in rural counties. As of 2015, 98 out of 101 rural Missouri counties were considered to be in a shortage of mental health professionals as defined by the Health Resources and Service Administration. Furthermore, rural Americans are considerably less likely to have health insurance that covers the costs of therapy or antidepressant drugs. This lack of both physical and financial access to mental health treatment leaves rural people at additional risk of suicidal ideation and attempt.

Figure 2: Mental health professional shortage areas in Missouri in 2025 – the problem persists. Light blue areas indicate St. Louis and Kansas City metro areas. Source: ruralhealthinfo.org

Rural communities are also far more exposed to firearms. In some sense, the results of my regression seem counterintuitive: since more rural residents already own a gun, fewer would need to purchase a new gun in order to end their life. However, a 2017 Pew Research poll found that 42% of rural households own zero guns. These households would be considered “exposed” to a waiting period rule – that is, if one of their residents intended to commit suicide with a gun, the outcome would be affected by whether they must wait between purchasing and receiving a gun.

Given the higher per-capita density of gun stores in rural areas, relaxation of waiting periods implies a greater jump in access for rural residents. Nearly 90% of suicide attempts with a firearm result in death, compared with 47% for jumping, 8% for drug poisoning, and 4% for cutting. Thus, preventing suicide by firearm does not simply alter the cause of death. Moreover, over 90% of those who attempt suicide do not go on to die by suicide; keeping a gun out of the hands of an individual in temporary, extreme mental distress can save their life for the long term.

Conclusion and Limitations

The findings of this research stand in contrast to the current gun policy landscape: in general, it is highly urban states that are more likely to have gun waiting periods, despite those waiting periods appearing to be more effective in rural counties. Of course, more evidence from around the nation will be needed to definitively conclude whether waiting period laws are more effective at preventing suicides in rural places. However, this indicates that rural policymakers should take renewed interest in implementing (and not repealing) waiting period legislation.

There are some important limitations to my findings that must be considered. As mentioned earlier, my analysis relies on the aggregation of county gun suicide rates by NCHS urbanization level, since individual county data is suppressed by the CDC due to privacy concerns. Therefore, any variation between Missouri counties of the same urbanization level remains unobserved. Furthermore, a significant portion of the increased gun suicide rate in rural Missouri counties relative to non-Missouri rural counties appears several years after the waiting period repeal in 2007. While this may simply indicate lagged effects of this law change, this could potentially be the result of unobserved changes in Missouri’s laws, economy, death reporting systems, or any other factor. Finally, the particular nature of Missouri’s repealed law – not merely a waiting period, but a permit system for purchasing handguns – means that this analysis cannot necessarily be generalized to other states’ waiting period laws.

Limitations aside, it is also critical to contextualize the regression results. While the effect of Missouri’s repeal of a de facto waiting period is highly significant, the size of that effect is relatively small. With 0.67 additional gun suicide deaths per 100,000 residents and a rural population of 1.8 million as of the 2010 census, an estimated 12 Missourian lives are lost every year due to the repeal of the waiting period (or 108 lives between 2008-2016).

This, admittedly, may not sound like many lives saved. Ultimately, it will be up to policymakers to weigh the upsides of firearm freedoms against the risk of self harm. Nonetheless, it is critical to remember that every suicide death is a real person – a farmer going through a stressful season, a teen facing severe bullying in school, or an elderly person struggling with isolation – and every death that can be prevented must be taken seriously.

|

Article by Caleb Rasor ’28 |

|