Article by Jennifer Lim

Following an unprecedented intentional shutdown of economic activity to fight the pandemic, switching it back on has caused a lot of turbulence. As the restrictions loosened, consumers armed with stimulus money entered a sluggish market with dysfunctional supply chains and significant labor shortages. This forced consumer prices in the United States to spiral up at the fastest pace in nearly 40 years, reaching a rate of 7% earlier this year. The US is not an anomaly–the entire world is experiencing inflationary whiplash as nearly every country’s inflation rates rose from the pre-pandemic years.

As a way to dampen such inflationary pressures, central banks like the Fed raise interest rates to curb borrowing and consequent spending by households and businesses. The Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) latest meeting brought the Federal Funds Rate up by another 0.75 percentage point to a range of 3.75% to 4.00%. Just nine months ago, the Fed funds rate was 0.25%. How are other countries’ governments responding to such inflationary fever? Are some tightening more aggressively than others?

To address this, we begin by examining the underlying mechanism behind rate adjustments. Central banks generally take into consideration a variety of factors that reflect the health of their domestic economy, the most prominent indicators being inflation and the GDP gap, a measure of how far current GDP is above or below a sustainable trend. To develop a baseline for ordinary behavior, we estimate the historic average response of short-term interest rates to inflation and GDP over the period 1970 Q1 to 2022 Q3 in a set of 32 countries that are evenly split between developing and developed economies.

As expected, we find that central banks have historically raised short term borrowing rates in response to both high inflation and a GDP gap. A 1 percentage point (pp) rise in GDP gap leads to a 0.19 pp increase in interest rates while a 1 pp rise in inflation corresponds to a 1.22 increase in rates.

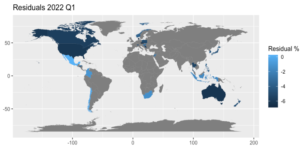

We then ask whether the recent abnormal conditions have led the countries to possibly deviate from their normal response.

Surprisingly, as the map indicates, most of the countries’ current interest rates lie significantly below the level that current economic conditions would have precipitated in our sample. That is, historically, when faced with these conditions, central banks would have set much higher rates than they are currently setting. Why would central banks all simultaneously be erring on the low side? We believe they are simply behind the curve in trying to catch up.

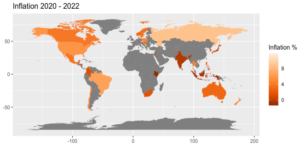

As the figure demonstrates, the rate of increase in inflation rates over the past 2 years are

eye-opening. After remaining subdued for decades, inflation in some countries has jumped by 5

or even 10 percentage points. Inflation rates have been climbing at such a fast pace over the past

two years that interest rates have not yet followed correspondingly. This is because central banks

are usually tentative when it comes to adjusting interest rates as minimal percentage shifts in

rates often bring lasting and far-reaching painful effects to every part of the economic system as

plans made by businesses and households for one interest rate environment must be revised.

Central banks prefer to allow the financial system time to adjust to rate hikes, implying a

maximal speed of rate increases. What our regression analysis of historic bank behavior suggests

is that this tightening cycle has a long way to go in most countries.