By Meghna Pamula

By Meghna Pamula

The past 25 years have witnessed a precipitous decline in American religiosity. Over the same 25 year period, America has become a much wealthier society, though that wealth has been spread increasingly unevenly. Studies show that a sense of faith or religiosity is associated with greater individual wellbeing in that higher levels of spirituality/religiousness are associated with lower levels of depression and lower levels of substance use. This raises the question: is religiosity also associated with greater economic wellbeing? One common view is that wealthy modern societies emphasize secular education in order to prepare people for prosperous jobs, and therefore undermine or do not leave room for religion. These competing views beg the question: are higher levels of religion and spirituality associated with higher or lower levels of economic prosperity?

Using data from the United States Census and the Pew Research Center, I explored the relationship between religiosity and economic prosperity in America. I used household income growth rate (from 2000 to 2020) as a measure of economic prosperity, and frequency of prayer and church attendance in 2020 as measures of religiosity.

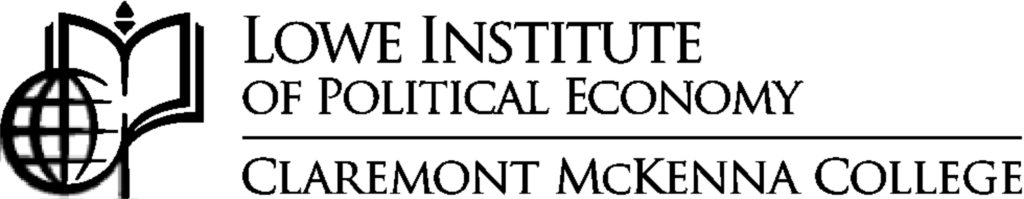

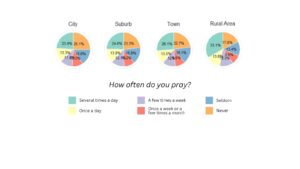

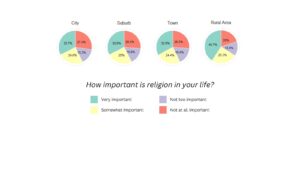

Before comparing the two variables I used the Pew Research Center data to explore differences in religious behavior across urban, suburban, and rural areas. The following pie charts summarizing religious behavior were all created using data from the year 2020.

Rural residents tend to report higher levels of religiosity. They are more likely to pray frequently than urban residents. The graph below shows that 33.1% of rural residents pray several times a day, compared to 23.9% of urban residents.

Rural residents also tend to consider religion as being more important, compared to their urban counterparts. 40.7% of rural residents reported religion to be “very important,” as compared to only 32.7% of urban residents.

These findings align with the common rhetoric surrounding the relationship between modernity and religiosity. However, when it comes to frequency of attending religious services, rural residents do not necessarily attend church significantly more than their urban counterparts.

This could mean that there are more people in rural areas who have a connection to God that is not mediated by church, in the sense that they are religious but their prayer practices are more important to them than their church attendance. Alternatively, it could mean that urban residents may be inclined to attend church despite lacking a strong personal relationship to religion, simply because church is a community gathering place and a place to build one’s social network.

Aside from the surprising lack of difference between urban and rural residents in the church attendance charts, these patterns suggest that religious attitudes and practices do depend on place-based cultural norms. These norms could potentially influence broader outcomes such as economic prosperity or household income.

Methodology:

To explore the relationship between religiosity and economic prosperity, I combined data from the United States Census and the Pew Research Center. I calculated the income growth rate for each ZIP code by comparing household income in 2000 and 2020. As a measure of religiosity, I used the frequency of prayer reported in 2020 by residents in each area.

To assess the connection between these two variables, I ran a regression of religiosity on income growth. This allowed me to examine whether religious engagement is more common in areas experiencing economic stagnation or prosperity. To account for local cultural and economic differences across states, I included state fixed effects in the model. This approach means that, for example, I am not comparing Idaho to New York, but rather, I am looking at how religious behavior differs between more prosperous and less prosperous ZIP codes within the same state. By isolating within-state variation, the analysis controls for broad, statewide cultural factors, providing a clearer view of how economic growth and religiosity relate on a local level.

Regression Analysis:

The regression analysis indicates a negative relationship between income growth rate and frequency of prayer. This suggests that individuals living in places experiencing strong income growth tend to pray less frequently. This finding aligns with long-standing sociological theories that economic prosperity is often accompanied by a decline in religiosity.

The inclusion of state fixed effects further reveals how regional dynamics shape prayer frequency. States like Mississippi and Alabama, for example, have higher religiosity at every level of income growth than states like Vermont and Massachusetts. These patterns highlight the deep-rooted role of regional culture in influencing religious behavior — with the South remaining a stronghold of prayer and religious participation.

However, the strong statistical significance in the regression implies that this association between income growth and lower prayer frequency is unlikely to be due to chance. In practical terms, it means that communities experiencing faster income growth are also those reporting lower levels of prayer. Given the nature of the regression, we cannot determine a causal relationship — this is purely correlational and likely reflects a blend of multiple underlying dynamics. For instance, it could be that economic prosperity enables or encourages more secular lifestyles, or that in wealthier, more individualistic societies, communal or spiritual forms of support are replaced with institutional or material ones. At the same time, it may be that less religious communities are more likely to prioritize educational or economic growth, leading to higher income gains.

The finding that higher income growth is significantly associated with lower frequencies of prayer aligns with the widespread assumption that material success is naturally accompanied by a decline in religiosity. One possible interpretation is that material comfort reduces the perceived need for spiritual support, or that economic systems incentivize values such as individualism, efficiency, and secularism over communal religious expression. Alternatively, in regions where religious institutions historically offered key forms of social infrastructure, rising income might replace these institutions with other forms of support or leisure.

|

Article by Meghna Pamula ’25 Data Journalist |

|