By Aaria Chandwani and Dhriti Sonthalia

When women move from the shadows of informal work into the formal economy, nations unlock economic potential—and women gain the power and freedom they deserve. In high-income Western countries, parental leave for both mothers and fathers is seen as a key policy to support women’s participation in the workforce. But does this hold true in developing countries? Focusing on Africa, we examine the relationship between parental leave policies and both the levels and trends in female labor force participation (FLFP). Surprisingly, we find that countries offering more generous leave for women tend to have lower FLFP, while those with more generous leave for men show higher FLFP—suggesting that balanced parental leave may be more effective in supporting women’s economic inclusion.

Combining data from WORLD Policy Analysis Center and labor statistics from International Labor Organization (ILOSTAT), we analyzed how female labor force participation in African countries relates to policy decisionsregarding paid parental leave, protection from domestic violence, and child marriage. Interestingly, while there was no significant correlation of labor force participation (LFP) with child marriage and domestic violence, the correlation with parental leave policies was notable.

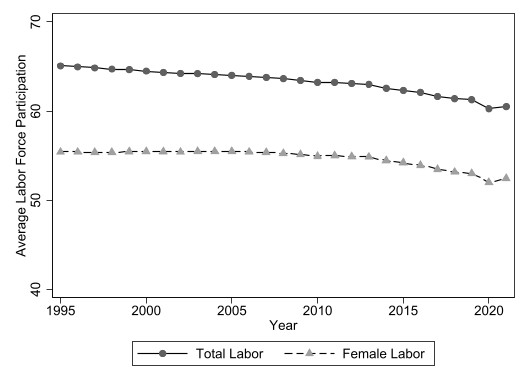

Before presenting our findings, it is important to highlight a key trend we observed in labor force dynamics. The labor force participation rate (LFPR) is the percentage of the civilian non-institutional population aged 16 and older who are either working or actively seeking work. Figure 1 visually represents the total and female labor force participation in African countries, showing a significant overall decline in female participation. This puzzling decline underscores potential opportunities for enhancing women’s participation in economies poised for growth. Expanding policies like paternal leave may be one way to help reverse the downward trend and reinvigorate overall labor force participation. It’s also worth noting that some of the observed patterns may be influenced by changes in how LFPR is measured. For instance, since 2014, discouraged workers have been included in the labor force, unlike earlier when they were only “marginally attached,” affecting the overall rate.

Our panel data regression analysis covering 50 African countries found that longer paid maternity leave is negatively associated with FLFP. Although this result was not statistically significant, it is consistent with prior literature from the World Bank that highlights how generous maternity leave can lead to lower female employment due to prolonged labor market detachment and associated opportunity costs for employers.

In contrast, our results show a significant and positive relationship between paid paternity leave and FLFP , reinforcing the hypothesis that shared caregiving responsibilities can facilitate women’s sustained labor market engagement. This outcome aligns with research which finds that the implementation of paid family leave policies—especially those that include fathers—can reduce maternal labor market detachment by up to 20% in the year of childbirth. By encouraging paternal involvement in early childcare, paternity leave may ease the re-entry of mothers into the workforce, thus promoting a more gender-equitable distribution of household and economic responsibilities. However, it is important to note that this relationship may be influenced by reverse causality or omitted variables, such as underlying cultural attitudes toward gender equality, which could drive both higher female labor participation and the adoption of progressive leave policies.

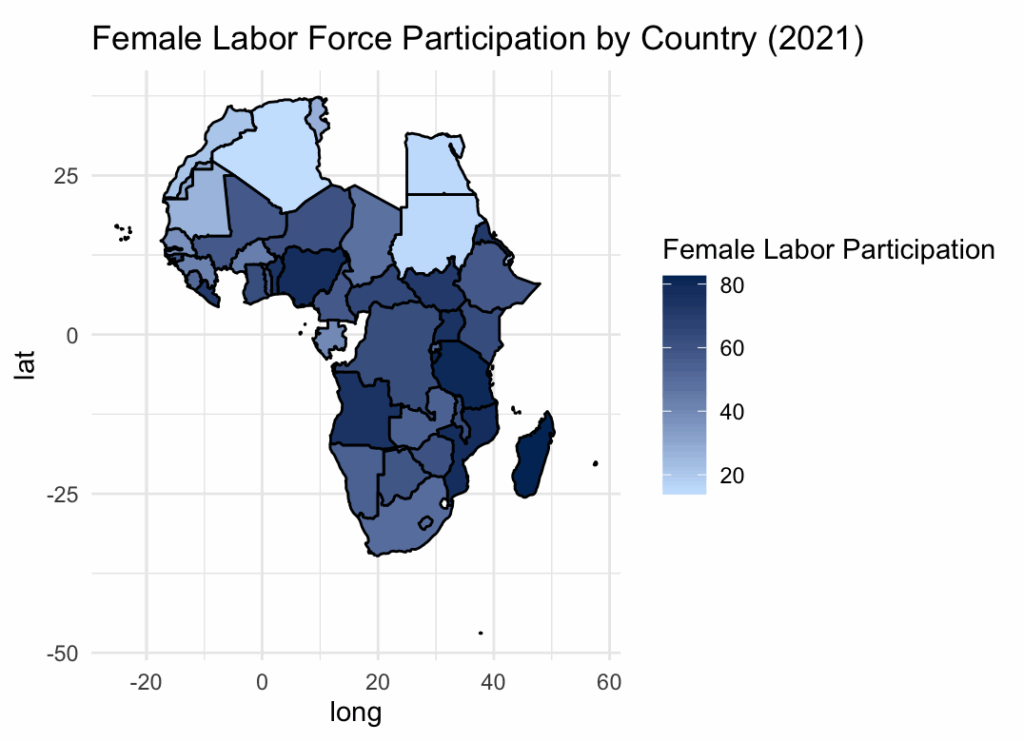

Figure 2 maps FLFP across African countries in 2021, revealing substantial regional variation. While countries in Eastern and Southern Africa exhibit relatively high participation rates, much of North and West Africa show markedly lower levels. This trend aligns with the regression result of Arab regions (North African countries) exhibiting significantly lower FLFP on average. Overall, this disparity suggests that other cultural factors play an important role in the dynamics of FLFP. There is also an opportunity for targeted policy reforms–such as increased paternity leave—to unlock untapped labor potential across the continent.

Surprisingly, variables often assumed to significantly impact female labor force participation—such as domestic violence and child marriage—did not yield statistically significant results in our regression analysis. This may be due, in part, to the limitations of available data. For instance, key legal variables—such as domestic violence laws and orders—are represented as binary (0/1) indicators, which fail to capture nuance in implementation, scope, or effectiveness across countries.

Expanding paternity leave can be a strategic tool for fostering inclusive labor markets, not only by promoting female participation but also by mitigating hiring biases against women of reproductive age. If the direction of causality can be established, we could conclude that improved paternity leave policies, likely by encouraging and enabling men to share home production, will enable African women to join the formal labor market.

|

Article by Aaria Chandwani ’27 and Dhriti Sonthalia ’27 Data Journalists |

|