Prices From Oil to Gas to Wallet

How much is the price of oil affecting the price of gas and the Inland Empire’s wallets?

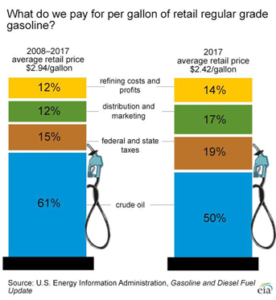

Over the past twelve months, oil prices have risen from $60 per barrel to $80 per barrel. Robust global economic growth, continued supply disruption in Venezuela, and potential renewed sanctions on Iran all represent risk that prices could rise still higher. In light of this, one pressing question for consumers is: how much will the increase in oil prices affect household expenditures on gas? Over the last century, oil prices have followed the same trend as gas prices. Between 2007 and 2016 the price of oil made up around 61% of gas prices. While the figure had declined to 50% by 2017, this still results in retail gasoline prices responding strongly to world crude oil prices. (Data Source: US Energy Information). The long run relationship is a $10 increase in oil results in a 25 cent increase in the per gallon price of gas (source: St. Louis Fed economists Owyang and Vermann). According to the Federal Highway Administration, the average number of miles driven per American driver is about 13,476 miles each year and the 2017 EPA estimates state that the fuel economy for cars is 24.7 miles per gallon. Thus, an average american driver uses 545.59 gallons of gas each year. Given the average gallons used by an American driver and that most commuters in the Inland Empire drive to work, usually alone, a 25 cent increase in gas price can cut into disposable income reserved for other economic activities by an average of $136.40 per year for each of the millions of IE drivers.

In the short run, gas is an inelastic good, the consumption of which is minimally affected by changes in price. Around 90% of workers in the Inland Empire drive to work every day, averaging a 31 minute commute. A staggering 78% of workers drive alone. In the event of rising oil prices, consumers will spend more of their disposable income on gas, having less disposable income to spend on other economic activities. With the increase in domestic oil production resulting from fracking, US oil imports have declined markedly from their peak in 2005. More of these higher payments will remain in the US. Nonetheless, as the Inland Empire is not an oil producing area, these extra payments will still be heading out of the local economy, reducing the money available for local services.

In California, increases in the price of oil have been compounded by the new California tax on gas of $0.12/gallon. The new tax was enacted at the beginning of this year to fund infrastructure improvements. Prop 6 on the ballot this November aims to repeal this tax, though that measure is predicted to be defeated. However, unlike gas prices due to increasing payments for oil, some part of the tax dollars will return to the local economy in support of infrastructure construction jobs and the infrastructure improvements themselves will be locally valuable.

While an increase in gas prices might not affect overall consumer demand, consumers are very price sensitive when it comes to choosing a filling station. According to a 2018 study conducted by the National Association of Convenience Stores, two-thirds of consumers were willing to drive five minutes away in to get a 5 cent per gallon decrease in the price of gas. In a competitive market, retailers cannot immediately pass on the increase in wholesale oil price to the customers by increasing that gas price because of fear of losing customers to their competitors and uncertainty regarding the actions of their competitors. Thus, filling stations delay increasing their price to keep their customers. However, it has the reverse effect when the price of oil decreases in that there will be a lag in the decrease in price of gas as retailers attempt to recoup the profits lost when oil prices increased. Thus, the price of oil and gas follow each other, but with a lag. Unfortunately for drivers, filling stations are twice as swift to pass along rising costs as they are to pass along falling costs. Within the first week of a 1 percent increase in oil prices, gas prices increase 0.52 percent. Within the first week of a 1 percent decline in oil prices, gas prices decline only 0.24 percent. (source: Radchenko and Shapiro Energy Economics 2011). In short, higher oil prices translate to a significant hit to IE household finances.